Pharmacists are highly trusted health professionals with expanding roles in the health care system. Your local pharmacist can administer vaccines, modify prescriptions, and may even have limited prescribing authority. Most pharmacists practice in community (retail) settings, and retail pharmacies are widespread, making more health services more accessible to patients. This is good news for patients.

In the United States, the majority of retail pharmacies are corporately owned, meaning the pharmacist is usually an employee, and not an owner. Independent and pharmacist-owned stores do exist, but they are shrinking in number. A consequence of corporate ownership of pharmacies beyond challenging work conditions for pharmacists is the lack of pharmacist influence over store practices, including which products may be sold in the store. As we have seen the scope and importance of the pharmacist grow over the past few decades, so has the appearance of unproven and pseudoscientific products on pharmacy shelves. Notably, homeopathy is now easy to find in almost any retail pharmacy.

What we should expect of pharmacists with respect to homeopathy is the context for a paper that I want to review (h/t Dr. Edzard Ernst) about pharmacy education and the teaching of homeopathy to pharmacists. The paper is entitled Teaching Homeopathy in U.S. Pharmacy Schools and it’s from Esra’a Khader and William R. Doucette at the College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa.

What’s the problem with homeopathy in pharmacies?

Homeopathy is an alternative-to-medicine practice which has persisted in use despite the lack of evidence showing it has any beneficial effects. Based on the idea that “like cures like” (essentially sympathetic magic), proponents of homeopathy believe that any substance can be an effective remedy if it’s sequentially diluted enough: raccoon fur, the fermented duck liver, even pieces of the Berlin Wall are possible remedies. The more dilute the remedy, the more powerful it is claimed to be. Typical remedies in use are so dilute that they are effectively and literally placebos, containing no active ingredients at all.

Homeopathy is incompatible with a scientific understanding of medicine, biochemistry, and even physics. However, when sold commercially, homeopathic “remedies” look like conventional medicine when they’re stocked on pharmacy shelves. The marketing and labeling that is permitted for homeopathic “remedies” in the United States does not draw attention to the lack of active ingredients. Consequently, it would be difficult for the average consumer, who may never have heard of homeopathy, to identify that some of the products on the shelf may be inert. XKCD highlighted the ethical issues with homeopathy in pharmacies several years ago (I have pasted the hover text below):

“I just noticed CVS has started stocking homeopathic pills on the same shelves with–and labeled similarly to–their actual medicine. Telling someone who trusts you that you’re giving them medicine, when you know you’re not, because you want their money, isn’t just lying–it’s like an example you’d make up if you had to illustrate for a child why lying is wrong.”

The Pharmacist’s Role

Before I dive into the paper, it’s worth pausing to ask what we would expect a science-based pharmacist to know about homeopathy. Given there is a lack of evidence to demonstrate that homeopathy is effective for any condition, and that its underlying principles are essentially sympathetic magic, the therapeutic aspect of homeopathy are straightforward. There are no medicinal effects.

Since homeopathy may be sold in a pharmacy (potentially against the wishes of the pharmacist), pharmacists need to be able to distinguish homeopathic products from conventional medicines, and be able to answer questions from patients about them. Ideally, pharmacists will understand core concepts of homeopathy so that they could contrast its ideas with the facts of biochemistry, physiology, and pharmacokinetics. Perhaps as part of a module on alternative forms of medicine, and the nature and effectiveness of placebo effects. With that knowledge, pharmacists would be well positioned to provide evidence-based information on the lack of efficacy for homeopathy and guide patients to effective treatments (or at minimum, avoiding unnecessary expense.)

The Research

This new paper from Khader and Doucette was an “explanatory sequential mixed methods approach” – effectively an online survey followed by interviews. This was not a survey of pharmacists, but of pharmacist educators. The authors’ stated objectives were to: 1) describe how and which homeopathy topics are taught in US schools of pharmacy and 2) characterize pharmacist roles with patients interested in using homeopathic products. The authors get off to a shaky start in the introduction, seemingly reluctant to point out the obvious:

Because these basic tenets conflict with modern medicine, pharmacology and therapeutics, the effectiveness of homeopathic products can be viewed skeptically by many pharmacists.

and

Since homeopathic products are legal drugs in the U.S., pharmacists should have a role in assuring their safe and effective use.

The first part of the research, the survey, was an email invitation sent to 3,300 pharmacy practice faculty in the USA. Two follow-up emails were then sent. 365 usable responses were received, which was an 11% response rate. While this method included multiple responses from a single pharmacy school, the authors state that there were responses from 95.8% of all pharmacy school.

Questions in the survey included faculty demographics, if homeopathy was taught at the school, how it was taught, which homeopathic topics were covered, and the methods used to teach them. Disappointingly, the authors note:

Questions were developed after reviewing educational resources provided by a homeopathic manufacturer (Boiron USA).

The manufacturer-based framing of homeopathy didn’t lead the researchers to ask potentially more useful questions about homeopathy. Importantly, if it was being taught uncritically as a practice, or if was being examined from a science-based perspective. While the authors noted that 61% of pharmacy schools have homeopathy in the curriculum, not enough information was collected to determine if this was a critical appraisal, or not:

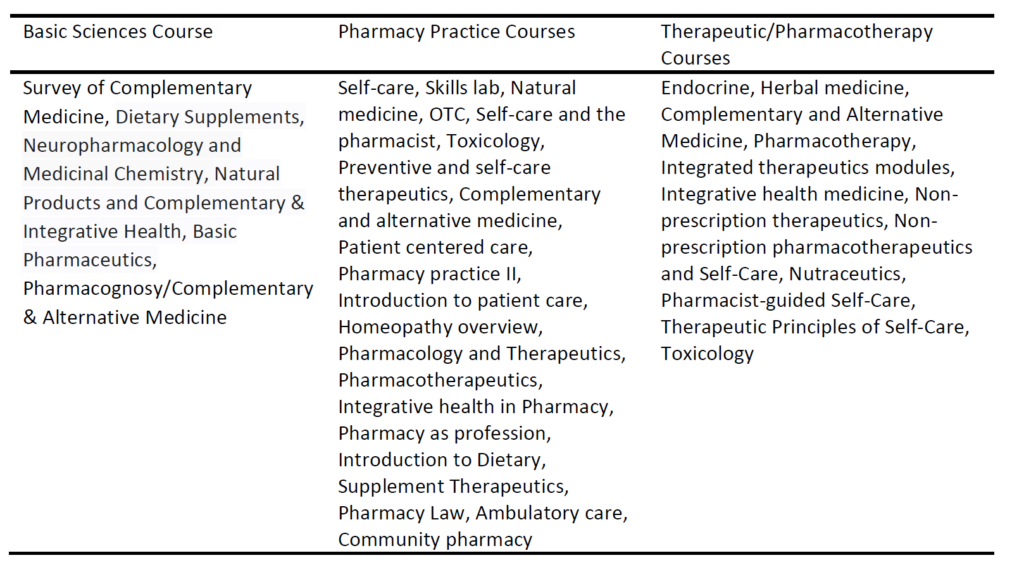

With regards to courses that incorporated homeopathy topics, 8 (5.8%) had them included in Basic Science Courses, 76 (55.5%) in Pharmacy Practice Courses, and 53 (38.7%) in Pharmacotherapy Courses.

Here are the titles of courses cited. While some of these may be critical in nature, it’s not clear for others.

In the second part of the study, 19 pharmacy faculty involved in teaching homeopathy were interviewed from 18 schools of pharmacy. Through these interviews, roles and themes related to homeopathy were identified:

- Pharmacists’ preparedness to guide patients for using homeopathic products.

- Themes: 1) recognize the difference between homeopathic and allopathic (sic) or herbal products, 2) counsel the patients efficiently and 3) the pharmacist needs to be knowledgeable.

- Ensure patients are getting benefits from using homeopathic products.

- Themes: 1) prioritize patients’ safety, 2) homeopathic remedies’ effectiveness and 3) triage the patient for the best use of homeopathy.

- Communicating properly with patients.

- Themes: 1) maintain your relationship with patients, 2) listen to, respect, and guide patients and 3) acknowledge that homeopathic products are available.

Unfortunately, there is not enough information from the interview summary to discern if the approaches being taken a pharmacy schools is critical or not. While some of the comments extracted from the interviews suggest this is happening, others do not.

Are pharmacy students critically appraising homeopathy?

Homeopathy has no place in science-based pharmacy practice, but the reality is that it’s being sold in pharmacies and drug stores. Pharmacists will inevitably be asked about their appropriateness and place in therapy. While homeopathy appears to be in the curriculum in a majority of American pharmacy schools, it is not clear if it’s being examined from a science-base perspective, or if pharmacists are being taught how to critically appraise the accumulated evidence that demonstrates it offers no meaningful health benefits. Understanding what pharmacy students are learning about homeopathy is a worthy topic. Unfortunately, this paper provides limited useful information on the subject, focusing more on the question “is homeopathy being taught” and not what is actually being taught. As they say, more research is required.